by Juanita Ryan

by Juanita Ryan

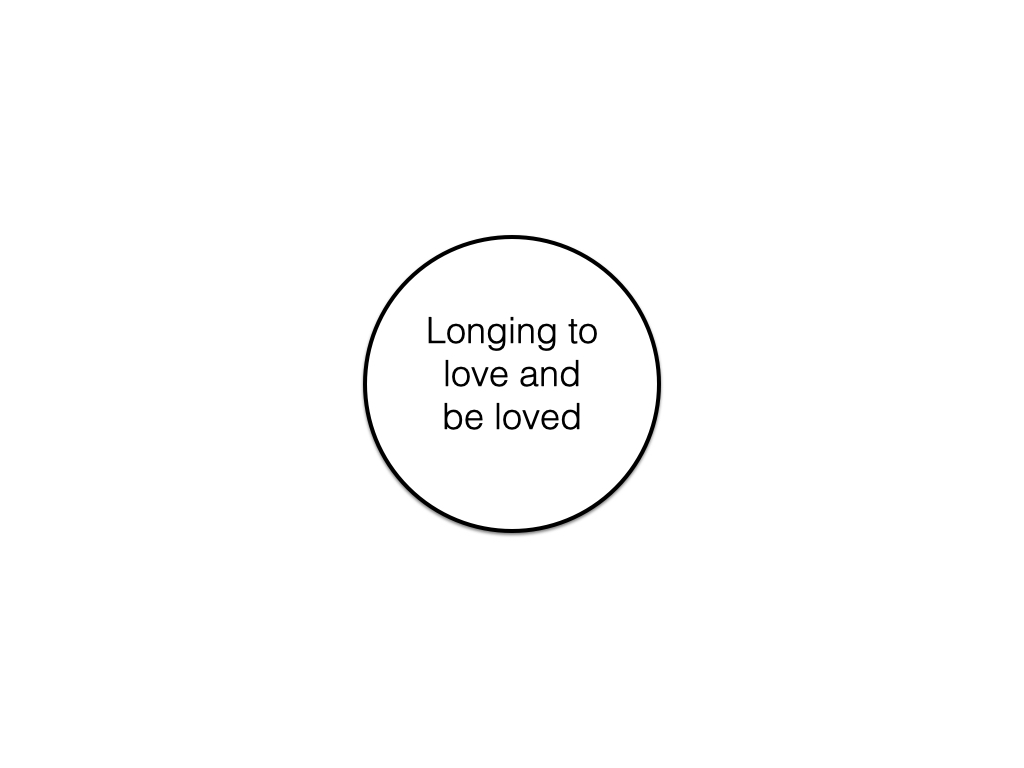

All of us long to love and to be loved. We long to both experience and express respect, kindness and acceptance in our relationships. We want to know and be known, to understand and be understood, to care and be cared for. To love and be loved.

But our relationships are often marked by tension, misunderstanding and distance rather than by the safety, empathy and closeness we desire. Even our most intimate relationships are at times anything but what we want them to be. For some relationships the periods of tension and misunderstanding are short-lived, but for other relationships distance, in the form of either avoidance or unproductive conflict, becomes the norm.

In my own relationships and in working as a therapist to help other people with their relationships, I’ve found that a significant part of the problem in our relationships grows out of our misperceptions of ourselves and of others. For a variety of reasons we lose sight of who we really are and of who the other person really is. Our fears and shame and our resulting defenses can blind us to the deepest truths about ourselves and about others.

Part I of this article has two purposes: first, to look at how fears and shame and resulting defenses make it difficult for us to see each other clearly, and second, to explore the destructive cycles that come from distorted views of ourselves and others. Part II explores practical strategies for moving past our defenses toward true intimacy in our closest relationships.

Seeing Ourselves Clearly My discussion of relationships in this article is based on a way of understanding ourselves that I explored in a previous article (see Seeing Ourselves More Clearly). I will begin by summarizing that article.

Love

Basically the answer to the question “Who am I?” is this: I am a person created in God’s image with a longing to love and to be loved. One of the things we know most fundamentally about God is that God is love. Because God has created us in God’s image, God has built into us a capacity and longing for love. Beneath all our distortions about ourselves, beneath all our ego and pride and defenses, we are creatures who long to love and be loved. At the most basic level, love is what our lives are about, what we are about, and who we are. We are people created to give and receive love. Our sense of meaning and joy in life come as we express our true selves in the giving and receiving of love.

The problem is, of course, that a lot stands in the way of our being able to fully experience our true selves. Both our capacity to love and our capacity to receive love can become distorted. How does this self that longs to love and be loved get so lost? How is it that we find ourselves competing with each other rather than cooperating in love?

How is it that we feel insecure and spend so much energy trying to prove ourselves, instead of knowing we are loved? How does it happen that we work to feel superior to each other rather than give ourselves in love and joy to each other? What happens to the true self?

Fear and Shame: The Enemies of Love

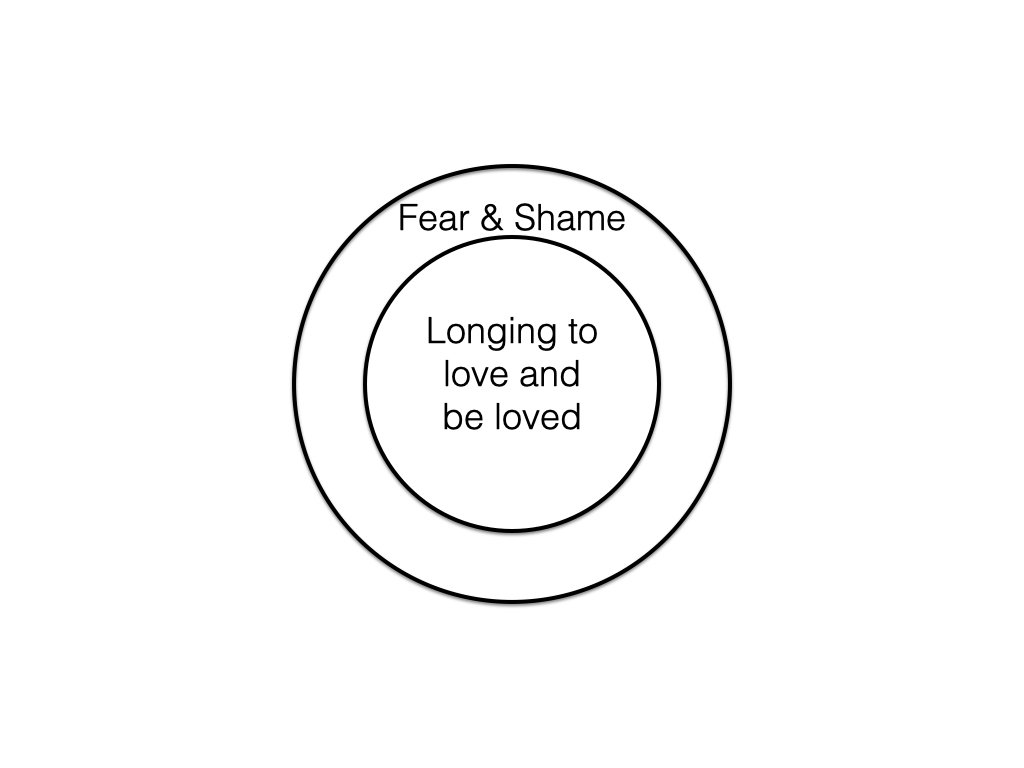

What happens to the true self, in simple terms, is that it gets lost in fear and shame. Fear and shame are the enemy of love. They prevent love from growing in us. They prevent love from being the center of our lives. Unfortunately, fear and shame can sometimes begin very early in life. As children we may have experienced events that threatened our well-being, events that were frightening for one reason or another. We may have heard angry voices or seen angry faces or felt ourselves being handled roughly. We may have unsuccessfully sought eye contact with a distracted or depressed caretaker. We may have been abandoned in some way. Or abused.

In all these situations it is as if our adult caretakers were holding up a mirror for us. Children look into the faces of their caregivers and believe they are seeing themselves, or the effects of their presence. If what we saw in that mirror as children was mostly a calm, loving and nurturing image, we would have believed that we were loved and that we were capable of loving others. But if we looked in that mirror and saw mostly anger, depression or anxiety, we may easily have believed that something was wrong with us. As children we had no way of knowing that the distress we were sensing was not a reflection of us. We would have seen ourselves in that distressed face and developed fears about ourselves, fears that we were not loved or that we were not loving.

If, in addition to this kind of distorted feedback, we experienced distressing words and actions, our worst fears would have been confirmed. If we were told that it was our fault that our caretaker was distressed, we would have believed that this was true. If our physical or emotional needs were neglected, we would have believed we had little value. If we were abused emotionally or physically or sexually by someone we thought we could trust, we easily could have believed we were at fault. If a parent died or left, we might even have believed we were the cause. Fears and shame of these kinds are normal in children who do not yet understand the complexities of life.

The most fundamental fears and shame that develop are that we are not loving or that we are not lovable. Fear and shame distort our ability to know and experience our true selves. We lose a clear sense of who we are—that we are loved and that we are capable of loving.

Defenses: Our Self-Protection Against Fear and Shame

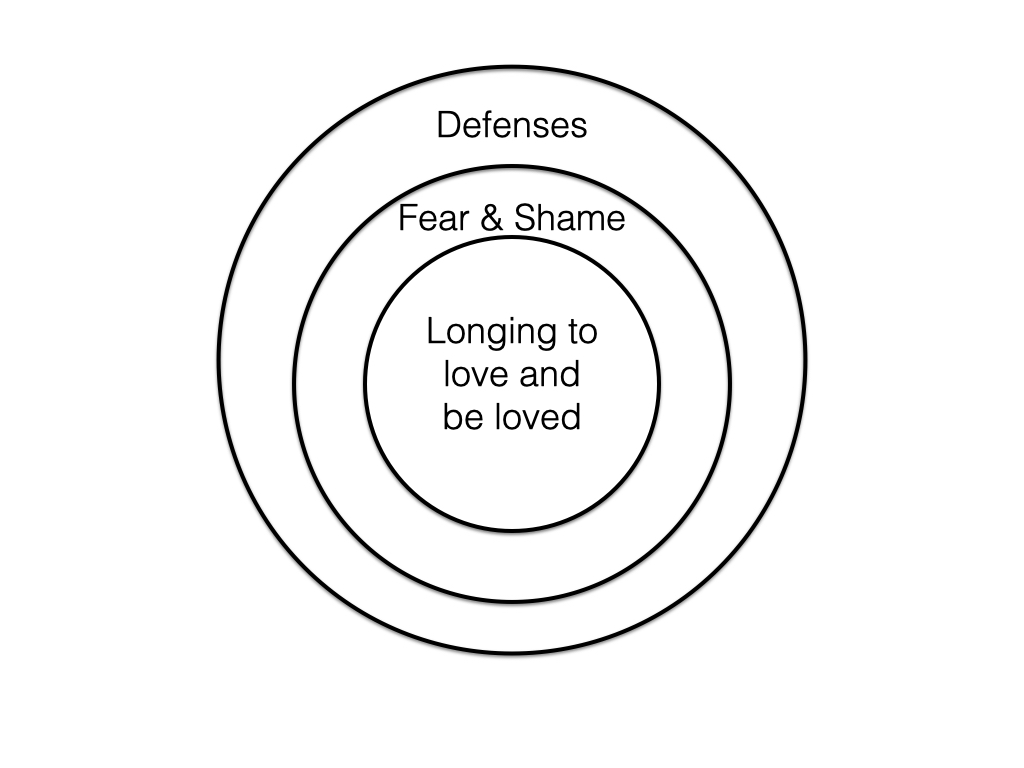

Our fears and shame and resulting distortions about ourselves generate painful feelings—feelings of anxiety and despair about ourselves. These feelings are too painful to tolerate for very long. So at the same time that our distortions about ourselves are being born, a strategy for protecting ourselves from the pain of these distortions is also born. We do not intentionally set about to protect ourselves from the painful effects of fear and shame. We do it instinctively, with little or no awareness of what we are doing.

Over time, these protective strategies can become more and more fixed in place, forming a defensive structure. This defensive structure tends to take on a life of its own. It becomes the way we define ourselves, the way we present ourselves to others and the way we experience ourselves. We can even come to think of our defensive structures as our true selves. But in reality our defensive structures are a kind of false self.

Over time, these protective strategies can become more and more fixed in place, forming a defensive structure. This defensive structure tends to take on a life of its own. It becomes the way we define ourselves, the way we present ourselves to others and the way we experience ourselves. We can even come to think of our defensive structures as our true selves. But in reality our defensive structures are a kind of false self.

Defensive structures come in a variety of forms. For example, if we fear that we are not loving, we might put a lot of energy into trying to please everybody. Or if we fear that our love is not wanted, we might become passive and withdrawn. If we fear that we are a “bother,” we might protect ourselves by preemptively withdrawing from relationships. If we are afraid we are not good enough, we might push ourselves to constantly overachieve. Or we might not ever try to achieve anything at all. We might become addicts. Or compulsive caregivers. Or compulsively religious persons. All these defenses are designed to protect us from the pain of experiencing our fears about ourselves directly.

At first these defenses seem to work. The fear and shame seem to be more under control. We don’t seem so vulnerable. And because our defenses seem to work, we can become very attached to these ways of being in the world.

It was, of course, creative and resilient of us as children to come up with ways to cope with life’s difficulties and the fears and shame that these difficulties created. But the long-term cost of our defenses can be very high. Over the long haul the defensive strategies that helped us cope as children can get in the way of our meaningful relationships in adulthood. If we do not find a way to regain access to our true selves, we become unavailable to ourselves and to others. Our defenses can create a fortress around our vulnerable, loving hearts, so that our true selves are walled off, locked away, lost to us and to others.

Defenses and Relationships

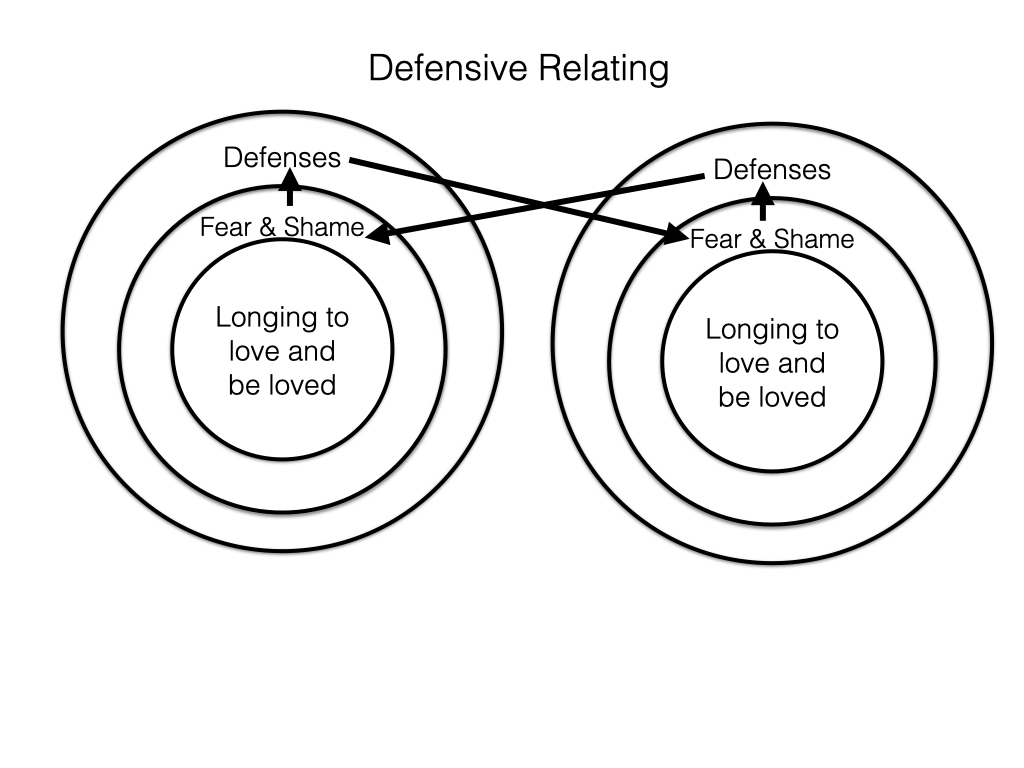

In the same way that we can lose sight of our true selves, we can also lose sight of the true selves of those with whom we have relationships. We sometimes act as if our defensive structures and the other person’s defensive structures are the real truth about ourselves and about them. When this happens our defensiveness can trigger the other person’s fears and shame and thus increase their defensiveness, which can, in turn, trigger our fears and shame and increase our defensiveness.

In these moments we have lost sight of the fact that everyone struggles with fears and shame of some kind, everyone struggles with defensive behaviors. And more significantly, we have lost sight of the deepest truth about who we are and who the other person is: We have forgotten the longing for intimacy that exists in each of us.

As a child I experienced many fears and a great deal of shame. Living with constant fear and shame would have been too painful, so I learned very early to try to manage my distress by hiding behind the protection of silence and pretense. I did not know it, but somewhere inside I felt like a big problem, so I tried to not be a big problem by focusing on other people and avoiding awareness of my own needs. I also unknowingly felt like I didn’t matter. So my goal was to let others know that they did matter. These defensive strategies have had significant negative consequences for all my relationships, including my marriage. I came into my marriage hopeful about love but unknowingly afraid, ashamed and defended.

My husband (I write this with his permission) had his own defenses connected with shame and fears about himself. His central fears were that he was not wanted and that he was not good enough. The main defensive strategies that he used as a child to protect himself against his fears were anger and withdrawal. And like me, he unknowingly brought his fears, shame and defenses into our relationship.

As you might expect, our defensive strategies created a destructive cycle between us that was almost entirely outside our awareness or understanding. For example, if I had a wish or a need, I would feel anxious about talking about it. For me, expressing a need or a longing would mean that I was a problem. I couldn’t afford to be a problem because I didn’t think I mattered. I didn’t see myself as having enough value to have legitimate needs or desires. So I would become silent and tense. I had almost no awareness of these fears. If I was aware of them at all, I experienced them as feelings of mistrust of my husband. I would find myself thinking, I can’t talk to him. I don’t know if he will understand or care. These thoughts were, of course, not really about him at all. They were projections of my own fears about myself. Without knowing it, I was turning a fear inside myself into a problem about him.

In situations of this kind my husband could sense the tension I was experiencing. And he could see my defenses. He could see my silence, my preemptive withdrawal, my hesitation to express my needs. What did all this mean to him? Because his defensive structure was rooted in fears of not being wanted, all those behaviors increased his fear of not being wanted or of not being good enough. His increasing fear would make him tense and angry. He would ask himself, Why doesn’t she want me? If she wanted me, she would talk to me more. Just as my unacknowledged fears and shame and resulting defenses got turned into a problem about him, he experienced his unacknowledged fears and shame and resulting defenses as being a problem about me. He would conclude that my tension and silence were indications that I did not want to be close to him, thus confirming his worst fears.

This was obviously all very confusing. And it became even more tangled. My behaviors confirmed his worst fear and shame: that he was not wanted or good enough. As his fear and shame increased, his defenses grew stronger. As his defenses grew stronger, I would see his anger and withdrawal as a confirmation of my fear and shame. I would start to think, I didn’t even say anything, and he’s angry. If I say anything, it can only get worse. So my fear and shame would increase, and my defenses would grow stronger, just as his did. And round and round the cycle we would go. Both of us feeling hurt. Both of us feeling we were in danger. Both of us feeling like the problem was the other person. Neither of us aware of our own fear and shame or the other person’s fear and shame. Neither of us aware of our own defenses or the other person’s defenses. And both of us grieving about the loss of closeness and safety we longed to experience with each other.

My fear and shame that I was a problem kept me tense and silent. This did indeed create a problem for my husband. And in that way, my worst fear came true; I was afraid that I was a problem, and now I was a problem. What I failed to understand, however, was that it was not my need or desire to talk that was the problem. It was my tension and defensiveness that came out of my fear and shame that was the problem. This vital distinction was very difficult for me to see when I was in the middle of feeling anxious and guarded.

My husband’s fear and shame that he was not good enough and that he was not wanted were confirmed if I acted as if he were unapproachable when he became tense and angry. But, of course, when he was defensive it was hard for me to be close to him, so his worst fears were coming true. The deepest truth, however, was that I did want very much to talk with him and I did want very much to be close to him. The problem was not that he wasn’t good enough or that I did not want him, but that I reacted to his tension and defensiveness and he reacted to mine.

Now, thank God, there was more to our relationship, even in those early years, when our fear and shame triggered our defenses. Much more. There was a great deal of love and hope and vision and courage. But the defenses got in our way much too often. When they were at their worst they left us feeling like enemies. In those times we lost the capacity to see ourselves and each other as people who longed to love and be loved. And this blindness left us with a deep sense of dissatisfaction and unhappiness about our relationship.

The Staying Power of Defenses

Defensive relating leads to unhappy relationships. But this dissatisfaction does not mean we will gladly or easily give up our defenses. Not at all. There are a number of reasons why we hold on to our defensive strategies.

First, our defensive patterns are the very behaviors that allowed us to feel we had some control in environments that were painful, threatening, lonely, chaotic or controlling. This false sense of control gave us some hope that we might survive with some small shred of dignity intact. Working, cleaning, isolating, helping others, staying angry, or staying loaded have the power to provide the false illusion that we have some control and that we may therefore survive.

A second reason we are deeply attached to our defensive patterns is that our hope for experiencing value is tied to them. Whether we are workaholics or we are addicted to pleasing or rescuing others or we are striving to be the perfect parent, we have come to think that our defensive patterns, this “false self,” is our only hope for gaining some sense of love or value in the world.

A third reason is that we are deeply attached not only to our defenses but also to our worst fears and shame about ourselves. The difficulty is that the fear and shame eventually became beliefs about ourselves. We do not see these ideas about ourselves as distortions, but as truth. And we instinctively try to protect ourselves from these terrible “truths” about ourselves by staying defensive.

Finally, another complication that increases the staying power of our distortions and defenses is that for every distortion we have about ourselves there is a matching distortion about others. If I believe that I am bad and that I deserve to be punished, I will see others as judgmental and harsh. If I believe that I don’t matter, I will see others as neglectful and dismissing. If I see myself as not good enough, I will see others as impossible to please. We believe that our worst fears and shame about ourselves are the truth, and usually without realizing it we project these distortions onto others, while looking for evidence to support our case against ourselves and against them.

Our fears and defenses can sometimes make it difficult to get back to the real truth, to the deepest truth. In the darkness of our defenses and fears, underneath the noise of all our communication with words and silences, we forget what is most deeply true: that we long to give love and be loved. We desire closeness; we are hungry for intimacy with each other.

Our defenses shut out the light, and we stumble around in the darkness, forgetting our value to our Creator and forgetting the value of the other person to our Creator—in other words, forgetting who we are and forgetting who the other person is. But God calls us out of the darkness of fear and shame and into the light of love. God calls us to see ourselves and each other in the light of love.

We will explore some pathways out of this darkness and into the light of God’s love in Part II of this article.