The integrative model for recovery from abuse assumes that ‘the problem’ is primarily inside the abused person. Makes sense. This assumption underlies most therapeutic strategies for recovery from abuse. But suppose you started with the assumption that ‘the problem’ is not primarily inside anybody but rather ‘between’ people? Suppose the problem was most fundamentally a relational problem? You come up with some different perspectives on the recovery process. These two perspectives are not incompatible, but they do offer different insights into the recovery process.

LECTURE NOTES:

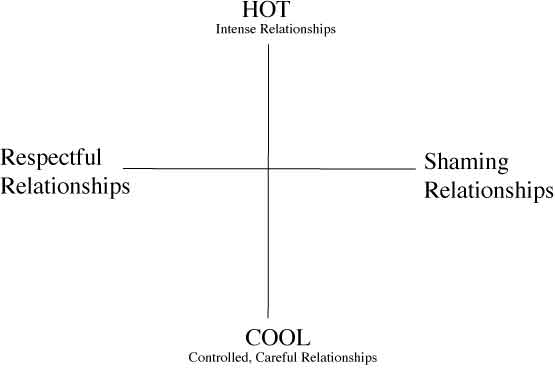

The best developed model of this kind comes from Facing Shame: Families in Recovery by Merle A. Fossum and Marilyn J. Mason (W. W. Norton & Company; 2Rev Ed edition 1989 — ISBN-13: 978-0393305814). Their model begins with observing that all relationships exist on a continuum from respectful to shaming. Along this axis there is a clear moral imperative: you should move from shaming relationships toward respectful relationships. In addition all relationships also exist on a continuum of intensity from hot to cool. There is no general moral imperative about this axis. We all need some relationships that are ‘hot’ and respectful but there is nothing wrong with having other relationships that are ‘cool’ and respectful.

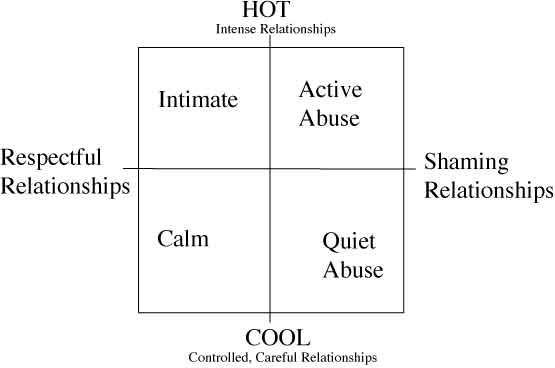

These two qualities of relationship lead to four general categories of relationships as shown in the figure below.

Just a few comments about each of these kinds of relationships:

ACTIVE ABUSE. Relationships that are ‘hot’ and shaming are actively abusive relationships. If the shame is manifested in domestic violence, for example, this is the kind of relationship where you see bruises, broken bones, trips to the emergency room etc. It is ‘hot’ meaning in-your-face, up-close, intense. And it is intensely shaming.

QUIET ABUSE. It is also possible for a very shaming relationship to be a ‘cool’ relationship. Rather than ‘up-close’ there is some distance in this relationship. It is not a healthy relationship but the level of intensity has gone down. A relationship of this kind may be characterized by emotional or verbal abuse rather than physical abuse. The shame is still there but there are fewer broken bones.

CALM. Calm means respectful but not intense. I have a calm relationship with the accountant who prepares my taxes each year. It is a respectful relationship but neither of us feel any urgency for it to me more than ‘calm.’ All of us need relationships of this kind in our lives.

INTIMATE. An intimate relationship is one characterized by both intensity and respect. Note that this is not really the opposite of an ‘actively abusive’ relationship. They actually have one thing in common — both are intense. If it is the opposite of something it is the opposite of ‘quietly abusive’ relationships. All of us need relationships of this kind in our lives.

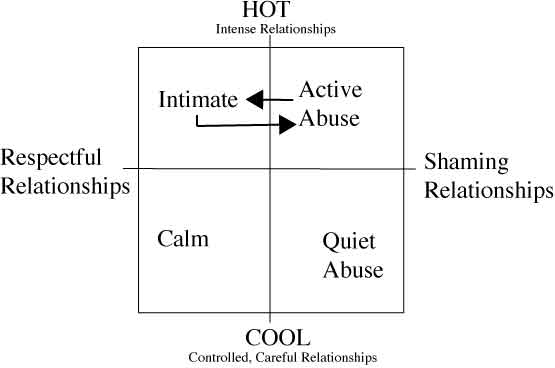

Now suppose you are in a relationship that best fits in the category: active abuse. Let’s use the example of domestic violence. You are being hurt. The shame is everywhere. And things are intense. What do people in such relationships want? Generalizations here are dangerous but my experience has been that a great many people in relationships of that kind want an intimate relationship instead of an actively abusive one. Nothing is more common after an incident of domestic violence than for the victim to urgently, passionately, desperately long for the relationship to be an intimate one. Perhaps the abuser has apologized. Promised that it will never happen again. Wept over their failure and pleaded for forgiveness. It might seem like intimacy is finally possible. And it might actually give some meaning to my current suffering if I could think of it as a kind of turning point that finally made possible the transformation of our relationship.

This is how people who have been physically abused in intimate relationships often feel. They are hoping that it is possible to move from an ‘actively abusive’ relationship directly to an ‘intimate’ one. The desired transition is as shown in the next illustration:

I have never seen this transition work. I guess you should never say never. . . but the odds of this being successful are very, very low. Sooner or later it will become apparent that the one-step transition to intimacy has left out some important steps in the healing process. There will eventually be a return to the old dynamics. It may take some time for the cycle of abuse to come back around to the ‘active abuse’ side of things. But it is quite predictable that this will happen. Important steps in the healing process have been ignored and the outcome is unfortunately quite predictable. So what are the steps that are being ignored? If the one-step-to-intimacy path just doesn’t work, what kind of pathway is available?

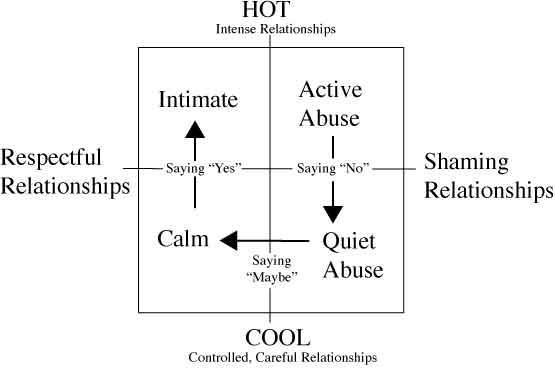

As shown in the next illustration, the path to intimacy can be understood has having three parts — which we will call “saying no”, “saying maybe” and “saying yes.”

A few words about each of these steps in the healing process:

Saying No. Healing begins by saying “no” to abuse. The “No” needs to be substantive. The time must come when we say “I won’t be part of this anymore.” There are predictable consequences to saying “no.” Other people will not be happy. And we will probably not be happy either. Saying “no” typically leads quickly to a sense of loss. And confusion — who am I now that things are not so intense? There is often a desperation to return to connection with the abusive person — the suffering we know often seems more survivable than the unknown suffering through which the healing process is leading us. Spiritual issues are also a prominent feature of this stage of the process. I know people who have returned to physically abusive relationships because they were convinced that God — an even bigger and more powerful bully — was just around the corner waiting to punish them for saying “no”. This view of God may seem terribly distorted to you (it is) but it is common among people who have been abused. Another dynamic common in this “saying no” stage is self blame. If only I had done something different. If only I had been more patient. If only. . . what-ever. The sense that I am at fault can become obsessional and lead people to retreat from the healing path back into active abuse.

It is important to emphasize that saying “no” does not suddenly turn an abusive relationship into a healthy one. The best you can hope for is a “quietly abusive” one. The shame is still there: it is probably still coming from the abusive person and there are still huge reserves of shame that have been internalized from earlier episodes of abuse. But “quietly abusive” is a step in the right direction. If we can get that far, we can then begin to explore the possibility of saying “maybe.”

Saying Maybe. The “saying maybe” stage of recovery is also challenging. Saying “maybe” is the kind of thing we do when we are aware of danger. Maybe we can spend time with this person without increasing our shame, maybe we can’t. The saying “maybe” stage is full of protective strategies. It has two main psychological manifestations: dissociation and hyper-vigilance.

Dissociation is kind of like having a ‘bunker.’ Part of me is going to stay safe in the bunker. I may come out to spend time with you, but I’m not putting everything at risk. Some of me will be safely hidden away. Dissociation is not a bad thing. It is an important skill which can save our lives in dangerous situations. It can, of course, also really mess up relationships if we use this tool when things are not actually dangerous.

Hyper-vigilance is also a common defensive strategy we use when we are saying “maybe.” If dissociation is like having a bunker, hyper-vigilance is like having an early warning radar system. We scan the horizon looking for signs of danger so that we can retreat before the danger becomes acute. Hyper-vigilance is not a bad thing. It is an important skill that can save our lives in dangerous situations. But, like dissociation, it can also make a mess of relationships when the situation is not really dangerous.

The important thing to remember is that we are trying to move from relationships characterized by shame to relationships characterized by respect. We are not trying to make the relationship more intense — that will have to wait for later. We are only trying to find out if it is safe. Is it possible to spend some time with this person without being abused? Without increasing our shame? If the answer is “yes” (and it may never be), then we may be able to move on to the saying “yes” stage of the healing process.

Saying Yes. In earlier stages of the healing process people look forward to this stage and think it should be the easy part. This should be when we see some payoff for all the hard work we have done. As a result people are often blind-sided by the difficulties of this stage of healing. The most common problem is that during this stage of healing we are moving from a calm relationship to an intense one — and the last time we were in an intense relationship things were very dangerous. So, even though we have said “maybe” for quite a while to test the waters, this saying “yes” stage can feel dangerous. One way of talking about this is the notion of “triggers.” Things will happen that remind us of how things used to be. And it is not reasonable to expect our response to these “triggers” to be rational or well proportioned. Even if we know better we may feel like things are the way things used to be. Sometimes it doesn’t take much for this to happen. A phrase, a smell, a situation. . .can suddenly drag us back to the angry, hurt, lonely feelings that we lived with for so long. Part of the work of the saying “yes” phase of healing is to come to terms with these triggers. With experience we learn that even though it feels like we have been drug back to square one, that’s not really what has happened. It is a powerful reminder of what is real about our history–and that is an important contribution which experiences of this kind can make to our lives. But we are not starting over. All the work we have done in the saying “no” stage and in the saying “maybe” stage help us to move much more quickly through the stages. Over time we find it easier to make our way back to present realities.

This way of thinking about the recovery process makes the most sense when applied to abuse in intimate relationships. I have for that reason consistently focused on domestic violence as an example. But it can also apply to other kinds of abuse. A few words about how this model might apply to recovery from spiritual abuse.

Recovery from Spiritual Abuse. Suppose that your relationship with God is both intense and full of shame–it is what we have called “actively abusive.” There are no broken bones. . . but there is the spiritual equivalent.

Saying No The first step in healing is to say “no”. You may want to say “yes”, to make that one-step move to intimacy with God. It has a lot of appeal. But, just as was the case in domestic violence, this quick fix never works. Sooner or later we will find ourselves back into a very shaming relationship with God. So we start by saying “no.”

It is probably important to emphasize that mainstream Protestant theology in America has almost uniformly emphasized that the spiritual life begins by saying “yes” to God. So you might not get much support for saying “no.” People might not understand how important it is. How necessary it is for long-term healing. Fortunately, the biblical text seems much more optimistic about saying “no” than you might expect. For example, saying “no” to idolatrous attachments is understood to be a necessary prerequisite for any spiritual growth:

You shall have no other gods before me. ((Exodus 20:3))

It is also worth noting that the spiritual brokenness which we feel when we are saying “no” to abusive relationships with God does not seem to offend God. On the contrary God seems attracted–comes close–to people whose spirits have been crushed:

The Lord is close to the brokenhearted and saves those who are crushed in spirit. ((Psalm 34:18))

Although we see our inability to say an unqualified “yes” to God as a kind of shame-full failure, God sees our spiritual brokenness in a completely different perspective:

The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit;

a broken and contrite heart,

O God, you will not despise. ((Psalm 51:17))

Notice that spiritual brokenness is understood to be a kind of worship (a sacrifice). God seems to understand that saying “no” is a step on the path to saying “yes.” May God be praised!

Saying Maybe. The next step in the healing process will be to say “maybe.” Don’t expect too much support here either. When was the last time you heard a sermon which suggested that God wanted your total commitment, with no reservations, no hesitations, no doubts? How can you expect God’s blessing if you are not totally sold-out-for-Jesus? But is God really like that? Consider the following texts:

- God Understands our Limits: “As a father has compassion on his children, so the Lord has compassion on those who fear him; for he knows how we are formed, he remembers that we are dust.” (( Psalm 103:13-14))

- God Accepts Limited Resources: “We have here only five loaves of bread and two fish,” they answered. “Bring them here to me,” he said. ((Matt. 14:17-18))

- God Accepts Limited Faith: “I do believe; help me overcome my unbelief!” ((Mark 9:24))

- God Accepts Limited Courage: Trembling and bewildered, the women went out and fled from the tomb. They said nothing to anyone, because they were afraid. ((Mark 16:8))

- God Accepts Limits in Ministry: “When I went to Troas to preach the gospel of Christ and found that the Lord had opened a door for me, I still had no peace of mind, because I did not find my brother Titus there. So I said good-by to them and went on to Macedonia.” ((2 Corinthians 2:12-13))

These texts confirm one of the most fundamental of biblical themes: that God’s love for us is secure. We do not have to be strong enough in our faith, diligent enough in our spiritual practices or anything else enough to be loved by God. If what we can honestly say to God is “maybe,” God understands that you can get somewhere from here, that this is a huge step forward from “no”–which was itself a huge step forward from simply tolerating an abusive relationship with a god-who-is-not-God.

Saying Yes. During earlier stages of recovery it usually seems like this should be the fun part. And there’s some truth to that. But the opportunities for triggers are everywhere. Because things are getting intense again it can feel very much like it used to feel. But, as we discussed earlier, the triggers are temporary, part of the process, and increasingly incapable of distracting us from the respectful nature of our growing relationship with God. One of the most interesting features of the “saying yes” stage of recovery from spiritual abuse is the changes which take place in our gut-feelings about God. In the saying “no” stage it usually feels like God is absent, in the saying “maybe” stage our feelings about God are volatile–sometimes close but dangerous, sometimes at a distance. But in the saying “yes” stage we look back and see things we could not see at the time. For example, we may look back to the experience of God’s absence in the saying “no” stage and realize that God was there with us helping us to say “no”. The spiritual emptiness we felt was a kind of excavation project in which God was preparing within us a more spacious place for his grace to eventually occupy. And the important thing about the experience of God’s silence now seems to be that it was a respectful silence–a kind of patience, a waiting for the right time to say a respectful word. Eventually it becomes clear that during the seasons of life in which we must say “no” or “maybe” God has been consistently saying “yes” to us. God was respectfully present saying “yes” to us when we could only say “no”. God was respectfully present all along when we were saying “maybe”–patiently, grace-fully responding in ways that allowed us to gradually decrease our dissociation and hyper-vigilance. May God be praised!

May God grant you the grace to say “no” when it is the time to say “no.” And the wisdom to say “maybe” when it is the time to say “maybe.” And the courage to say “yes” when that time comes. Whatever stage you are in the recovery process you remain a precious, lovable, fallible child of a gracious Father.